In the sources of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries from what is now East Belgium, there are repeated reports of soldiers being quartered, of wars, looting, town fires, plague, disease, crop failures and hunger. Reading these sources, life appears as a daily struggle for survival. Not until the second half of the 18th century did a prolonged period of peace allow for a calmer life and a general economic upswing.

However, the sources also show that people accepted such unfavourable living conditions and did everything to make the best of the lives they had. Hence, hardship contrasts with impressive successes, which simultaneously bear witness to a globalised world. Four regional examples illustrate this.

Galmei, a zinc ore, has believed to have been mined at Altenberg, near La Calamine (today: Kelmis), since Roman times. In the early modern period, the operators of the mine supplied copper smelters from Aachen, Namur, or Antwerp. They also built up a trade in calamine ore to Nuremberg, Sweden, and Lorraine, which, however, the many wars of the time repeatedly interrupted. In the 19th century, the mining company ‘Vieille Montagne’, which was based in La Calamine, became a globally active group.

There is evidence of a cloth factory in Eupen from the 16th century onwards. It enjoyed great privileges from the Dukes of Limburg. Shearmen, in particular, were indispensable and skilled workers who quickly moved in large numbers to where they were offered the best opportunities to earn money. Eupen weavers, shearers, and cloth merchants worked in nearby towns such as Aachen, Monschau, and Verviers, as well as in more distant regions such as Flanders, northern France, the Netherlands, and what is now Poland. The town of Eupen developed into an important cloth-making town in the 17thcentury. Eupen fine cloth was sold all over Europe. During Napoleon’s economic blockade against England (1806-1813), which briefly eliminated English competition, the Eupen cloth industry reached its peak.

Excellent clay, extensive deciduous woodlands providing the fuel, as well as good connections to routes of transport were the prerequisites for Raeren’s earthenware production from the 14th century onwards. During the heyday of the Raeren pottery, probably more than 100 potter families produced the coveted goods. They were traded in Cologne, Nijmegen, Liège, and Antwerp, from where they were exported to Asia, America, Africa, and Australia.

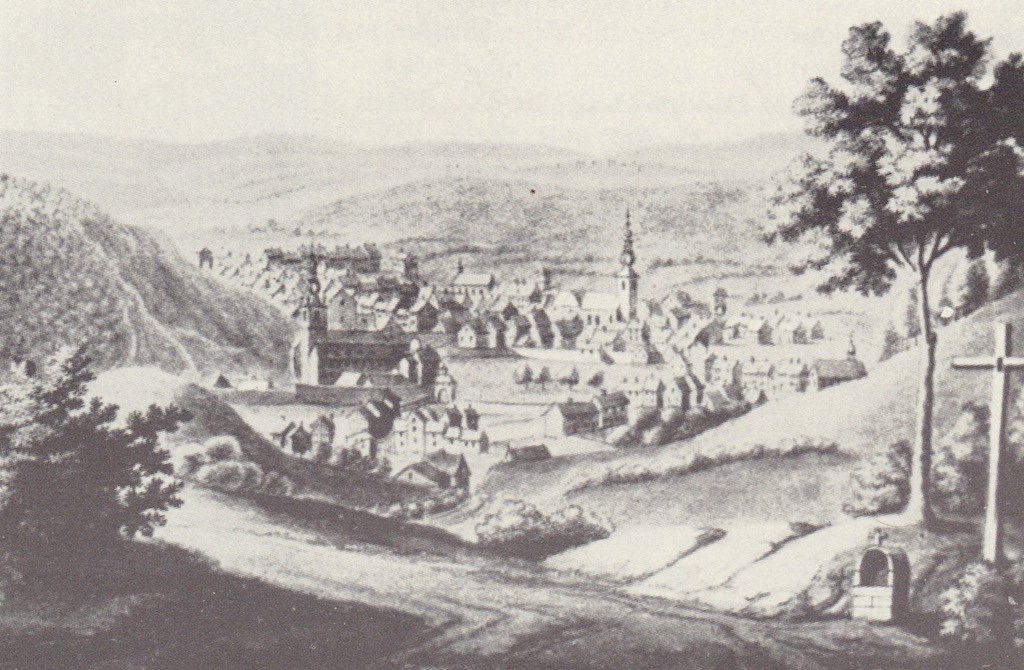

Even the remote Eifel region with the small town of Sankt Vith was well connected in the area between the Rhine and the Meuse, being where two important trade routes intersected. People had modest incomes from agriculture, yet they were able to build up their own livelihoods as middlemen with leather, livestock, and trade goods, or got involved in the haulage business.

Numerous wars and the destruction and hardship they brought repeatedly clouded the people’s prospects in the region (and elsewhere). For those aspiring to extend their agricultural activity to handicrafts or trade, open access to other regions and their markets promised prospects for the future as this included the option of trading regional or supra-regional products. Well-functioning networks were hence a necessity.

This period (the 18th century) is remembered in the Eupen region as the heyday of the cloth industry and the art of pottery, and for the Belgian Eifel as a time of hardship. The affiliation to the duchies of Limburg and Luxembourg and the consolidation of the German-French language border during this period became misused arguments to lay claims to the region’s national affiliation, notably in the 20th century. Conversely, the many facets and richness of everyday life and global economic relations was largely neglected until a few decades ago.

Wine from Chile, strawberries from South Africa in winter, or tea from India are just as normal today as laptops, mobile phones, or shoes from China, jeans from Bangladesh, or T-shirts from Vietnam. Such global networks are far from new. The early modern period saw the spinning of important threads of this network, and for this, today’s East Belgium is no exception. What are the consequences of these networks? Whom does it serve: the craftsman, the manufacturer, the trader, the customer? Only one, several, or even all? Who is disadvantaged by it and why? Does it help to ensure that our earth will still be a planet worth living on in a hundred years’ time?