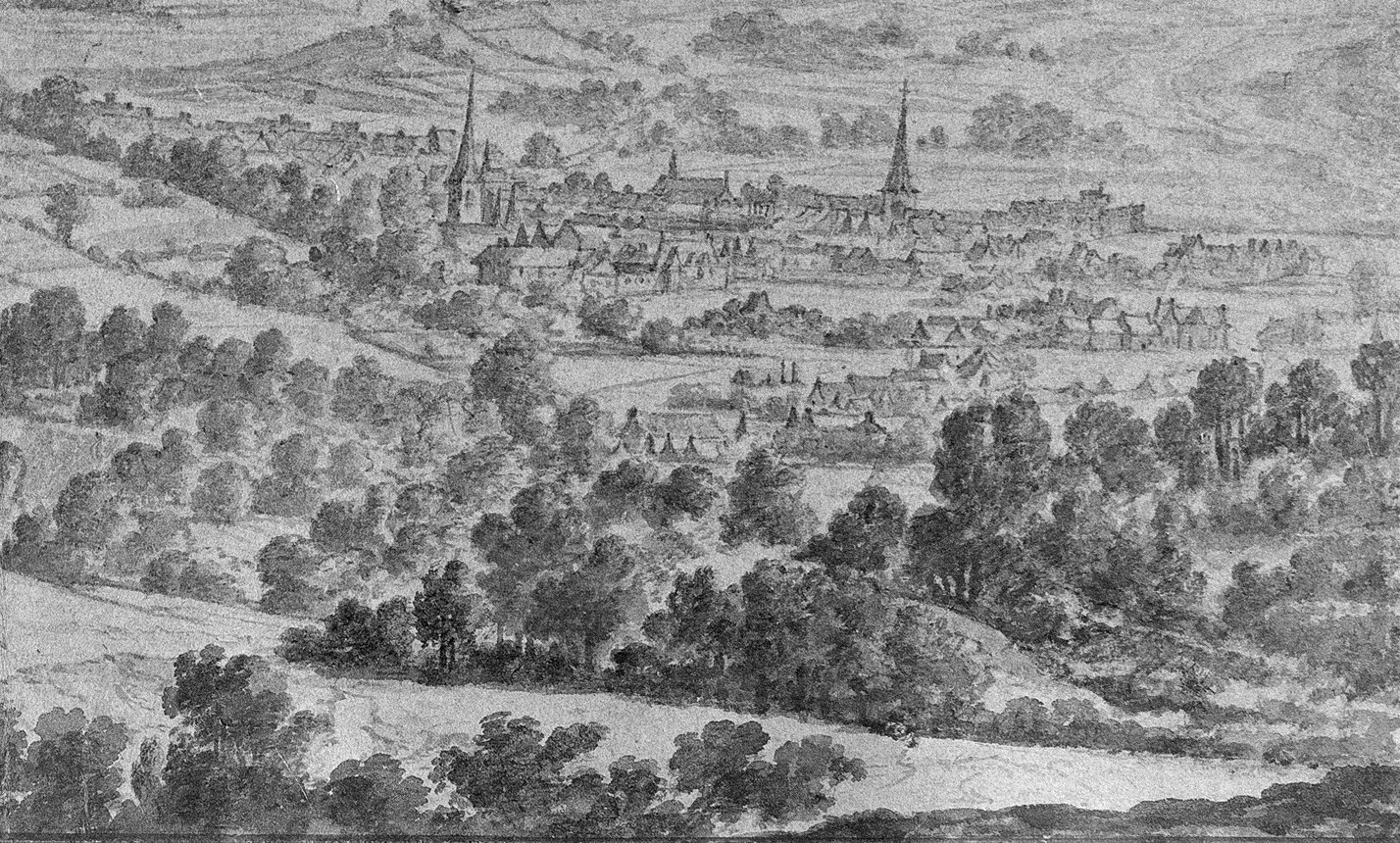

The area now known as East Belgium had been assigned to the Kingdom of Prussia at the Congress of Vienna (1815), where it formed the districts of Eupen and Malmedy. When these were assigned to Belgium in the Treaty of Versailles, the term ‘cantons rédimés’ appeared in French in reference to other European border areas that changed countries. The verb ‘rédimer’ means to ‘redeem’ or to ‘liberate’. According to this narrative, the area was liberated as a result of the German defeat and through its annexation to Belgium.

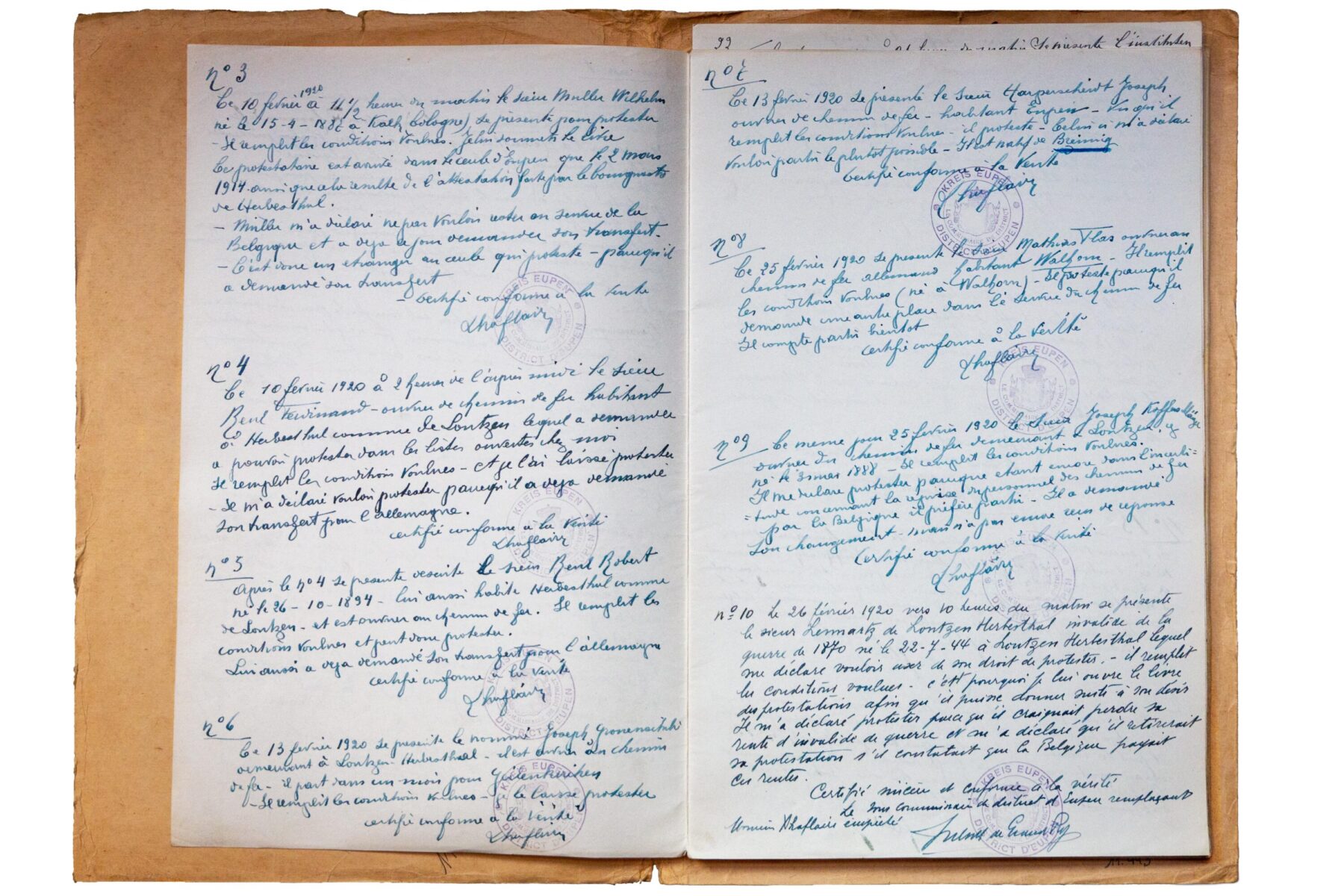

Article 34 of the Treaty of Versailles laid down the implementation modalities of the so-called ‘public expression’ (as it was worded in the Treaty) in Eupen-Malmedy. These were unique in that no similar measures were taken in any other border area. This ‘popular consultation’ (as it was worded in most publications) was not a secret and independent vote, but was merely intended to maintain the appearance of the people’s right to self-determination. Anyone who wanted to protest against the annexation to Belgium could only register by name in front of Belgian officials after justification in lists in the small towns of Eupen and Malmedy. There were numerous attempts at interference as well as protests from both the Belgian and German sides. In the end, the affected population was so unsettled that only a few signed the list. In collective memory, this incision was so strong that the ‘referendum’ all but eclipsed the memory of the First World War.

-

Judith Molitor

Opinion:

‘At this point, it is important to point out the remarkable imbalance in the culture of remembrance on both sides of the border: while the survey made such waves in Belgium, it went (almost) unnoticed in the [German] Eifel, for example. That is, while contemporaries certainly noticed, even for my grandparents’ generation (i.e. the cohorts from the mid-1920s onwards), it played such a minor role that I personally only learned about it (and only marginally!) in high school.’

The terms ‘pays / territoires / cantons rédimés’ are common terms in the press towards the end of the war to speak of border areas that have been or should be assigned to other countries on the basis of historical arguments. This also applies, for example, to areas ‘reclaimed’ by Italy or France from a nationalist point of view. Even during the war, Belgian diplomats and politicians advocated the notion of the ‘de-annexation’ of German border territories that had coincidentally been assigned to Prussia in 1815. In the end, however, it was simply economic and strategic arguments that persuaded the Allies in Versailles to allocate Eupen-Malmedy to Belgium as compensation. From a Belgian nationalist point of view, the territory of today’s East Belgium was thus ‘reclaimed’ after 105 years of Prussian rule. This explains terms such as ‘cantons rédimés’ or ‘rediscovered brothers’.

-

![Michel_Pauly]()

Michel Pauly

Opinion:

‘In Luxembourg’s culture of remembrance, there are endless narratives about how, when, and where the American forces liberated Luxembourg in 1944-45. The American soldiers were celebrated as liberators when they entered Luxembourg as they liberated or redeemed the population from the hated Nazi rule. Through the redemption of the ‘evil’ – the Germans – by the ‘good’ – the Americans – everyone can remember positive experiences with the Americans and negative ones with the Germans, while few today want to remember the reverse. The liberation of Luxembourg by the Americans certainly had and still has positive consequences for Luxembourg, but the demonisation of the one and the simultaneous heroisation of the other led to a black-and-white thinking in collective memory, which today makes it difficult for Luxembourg historiography to portray the relationships between Luxembourgers and the German occupiers on the one, and Luxembourgers and the American liberators on the other side.’

-

![Claudia Kühnen_Aachen]()

Claudia Kühnen

Opinion

‘The history of ‘Germany’ is also marked by the question of its own identity. From a number of tiny principalities to a German Empire in 1871, to Prussia and the ‘lost’ parts of Alsace, contemporary Poland, the Eastern Cantons etc., the German borders have always been blurred and constantly changing. Even von Fallersleben’s ‘Song of the Germans’, which eventually became the German national anthem, deals with what constitutes ‘Germany’ and ‘the Germans’.’